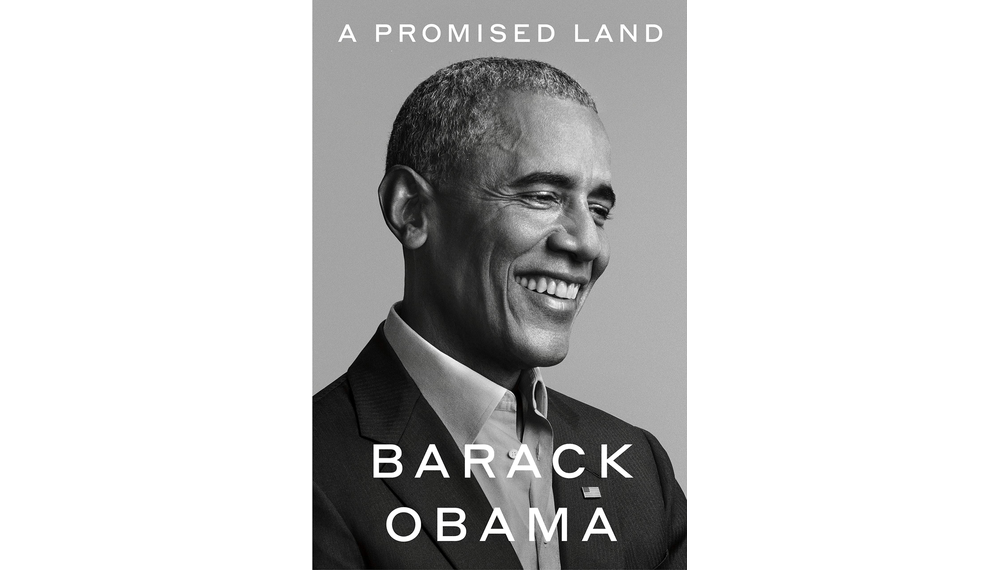

A Promised Land

A riveting, deeply personal account of history in the making-from the president who inspired us to believe in the power of democracy

요즘 들어 자서전을 많이 읽고 싶단 생각이 든다. (좋은 쪽으로든, 나쁜 쪽으로든) 자기 분야에서 큰 영향을 미치는 사람들은 달라도 뭔가 다르지 않을까 하는 호기심, 인생 선배의 이야기를 들어보고 싶은 마음 때문인 듯 하다. 어느새 타지에서 직장인으로 보낸 시간이 2년이 넘어간 만큼 인생의 방향을 고민하게 되는 시기이기도 하고.. 여러 자서전 가운데 오바마의 자서전을 먼저 읽어보기로 한데는, 인종적/지역적/문화적 마이너리티에 속한 그가 어떻게 미국 정치의 정점에 오를 수 있었는지도 궁금했기 때문이다.

책은 총 7파트로 구성되어 있는데, 오바마가 상원의원에 오를 때까지의 이야기를 담은 The Bet, 대통령 선거 당선될 때까지를 다룬 Yes We Can, 대통령 첫번째 임기를 수행하며 겪은 여러 문제들 (미국 국내 정치 상황, 2008 서브프라임 사태 해결을 위한 국제 공조, 태러와의 전쟁, 중국-러시아 등 경쟁국들과의 외교, 오바마케어를 비롯한 여러 정책 문제 등등)을 소개한 Renegade, The Good Fight, The World As It Is, In The Barrel, On The High Wire 등으로 이루어져 있다. 전문 작가가 아니지만, 글도 잘써서 그런지 각 챕터가 마무리 될 때마다 묘한 감동과 여운이 남았던 것 같다.

책을 읽으며 오바마의 몇 가지 특징을 발견할 수 있었다.

우선 오바마는 매우 매우 낙천적인 성격을 가졌다. 중요한 결정을 내릴 때, (무모할 만큼은 아니지만) 승률보다는 도전의 가치를 더 중요시 여긴다. 부정적인 상황보다는 억지로라도 긍정적인 요소에 집중하는 모습도 보이고, 일이 잘 안되었을 때의 리스크에 대해서는 그닥 겁을 내지 않는다. 현실적인 성격을 가진 미쉘 입장에선 답답할 노릇이다. 오바마는 그 이유를 스스로 돌이켜 보건대, 아무 걱정거리 없이 하와이에서 편한 생활을 했던 유년시절이 그런 낙천적인, 긍정적인 성격의 배경이 된 것 같다고 설명한다.

또 다른 중요한 특징으론, 현실보다는 이루고자하는 꿈에 집중한다는 점이다. 그렇다고 그 꿈이 구체적으로 정의되어있지도 않다. 목표보다 꿈이란 말이 더 어울리는, 조금은 추상적인 방향성을 갖고 일을 추진해 나간다. 요즘 유튜브를 보면 구체적인 목표를 새우고 지속적으로 성취 과정을 평가하면 성공을 이룰 수 있다는 영상이 많이 보이는데, 오바마는 그 반대의 사람인 것 같다. 그의 애매모호한 방향성은 매순간 전략을 바꿀 수 있는 유연성을 주었고, 그의 허황되 보이는 큰 꿈은 능력있는 사람들을 매료시켜 구체적인 일이 이루어 질 수 있게 하는 원동력이 되었다. 삼국지로 치면 유비와 같은 성향과 매력(삼국지 게임에서 항상 만점으로 평가되는!)을 가지지 않았나 하는 생각이 든다.

그의 체력과 자기관리도 본받고 싶은 부분이다. 50세 가까운 나이에 대선에 도전하면서 견뎌야 했던 일정을 보면, 30대라도 쉽게 견디기 힘들어 보이는 격무 그 자체였다. 이른 새벽에 일어나 하루 일정을 마치고 집에 돌아오면 밤 9시나 10시를 넘기는 것이 일상이었고 매주 두 세번은 다른 주로 가는 비행기에 올라타야 했다. 오바마는 그런 삶을 버티기 위해 매일 새벽에 달릴 트레드밀을 확보하는데 매우 신경을 썼다고 한다.

아래는 앞으로 종종 다시 보고 싶은 문장들을 옮겨와 봤다.

Quotations

For those young people.

More than anyone, this book is for those young people - an invitation to once again remake the world, and to bring about, through hard work, determination, and a big dose of imagination, an America that finally aligns with all that is best in us. (p.xvi)

Which kind of person do you want to be?

Once, when she discovered I had been part of a group that was teasing a kid at school, she sat me down in front of her, lips pursed with disappointment. “You know, Barry”, she said. (…) “there are people in the world who think only about themselves. They don't care what happens to other people down to make themselves feel important. Then there are people who do the opposite, who are able to imagine how others must feel, and make sure that they don’t do things that hurt people.” “So”, she said, looking me squarely in the eye. “Which kind of person do you want to be?”. I felt lousy. As she intended it to, her question stayed with me for a long time. (pp.6-7)

I did find refuge in books.

I didn't talk to anyone about this, certainly not my friends or family. I didn’t want to hurt their feelings or stand out more than I already did. But I did find refuge in books. The reading habit was my mother’s doing, instilled early in my childhood (…) Go read books, she would say. Then come back and tell me something you learned (p.9)

Much of what I read I only dimly understood; I took to circling unfamiliar words to look up in the dictionary, although I was less scrupulous about decoding pronunciations - deep into my twenties I would know the meaning of words I couldn’t pronounce. (p.10)

Build power not by putting others down but by lifting them up.

I saw the possibility of practicing the values my mother had taught me; how you could build power not by putting others down but by lifting them up. This was true democracy at work - democracy not as a gift from on high, or a division of spoils between interest groups, but rather a democracy that was earned, the work of everybody. The result was not just a change in material conditions but a sense of dignity for people and communities, a bond between those who had once seemed far apart. (p.11)

I lived like a monk.

For three years in New York, (…) I lived like a monk - reading, writing, filling up journals, rarely bothering with college parties or even eating hot meals. I got lost in my head, preoccupied with questions that seemed to layer themselves one over the next. What made some movements succeed where others failed? Was it a sign of success when portions of a cause were absorbed by conventional politics, or was it a sign that the cause had been hijacked? When was compromise acceptable and when was it selling out, and how did one know the difference? (p.11-12)

Big idea and nowhere to go.

Such was my state when I graduate in 1983; big idea and nowhere to go. There were no movements to join, no sselfless leader to foloow. The closest I could find to what I had in mind was something called “community organizing” - grassroots work that brought ordinary people together around issues of local concern. After bouncing around in a couple of ill-fitting jobs in New York, I heard about a position in Chicago, working with a group of churches that were trying to stabilize communities racked by steel plan closures. Nothing grand, but a place to start (p.14)

If it doesn’t work, it doesn’t work.

As law schoold was coming to an end, I told Michelle of my plan. I wouldn’t clerk. I'd move back to Chicago, try to keep my hand in community work while also practicing law at a small firm that specialized in civil rights. If a good opportunity presented itself, I said, I could even see myself running for office (…) “I can try, can’t I?” I said with a smile. “What’s the point of having a fancy law degree if you can’t take some risks? If it doesn’t work, it doesn’t work. I’ll be okay. We’ll be okay” (p.22)

Magic beans, baby. Magic beans.

She looked at me and shook her head, incredulous. “I can't believe you actually pulled this whole thing off. The campaign. The book. All of it.” I nodded and kiss her forehead. “Magic beans, baby. Magic beans.”

Why me?

“So my question is why you. Barack? Why do you need to be president?”

“Why me?” (…) “There's no guarantee we can pull it off. Here's one thing I know for sure, though. I know that the day I raise my right hand and take the oath to be president of the United States, the world will start looking at America differently. I know that kids all around this country - Black kids, Hispanic kids, kids who don't fit in - they'll see themselves differently, too, their horizons lifted, their possibilities expanded. And that alone … that would be worth it.”

Do you feel lucky?

“I guess the question for you, Mr. President, is, Do you feel lucky?” I looked at him and smiled. “Where are we, Phil?” Phil hesitated, wondering if it was a trick question. “The Oval Office?” “And what's my name” “Barack Obama.” I smiled. “Barack Hussein Obama. And I'm here with you in the Oval Office. Brother, I always feel lucky.” I told the team we were staying the course.